Abstract

Purpose

Despite the well-established health effects of socioeconomic status (SES), SES resources such as employment may differently influence health outcomes across sub-populations. This study used a national sample of US adults to test if the effect of baseline employment (in 1986) on all-cause mortality over a 25-year period depends on race, gender, education level, and their intersections.

Methods

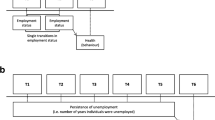

Data came from the Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL) study, which followed 2025 Whites and 1156 Blacks for 25 years from 1986 to 2011. The focal predictor of interest was baseline employment (1986), operationalized as a dichotomous variable. The main outcome of interest was time to all-cause mortality from 1986 to 2011. Covariates included baseline age, health behaviors (smoking, drinking, and exercise), physical health (obesity, chronic disease, function, and self-rated health), and mental health (depressive symptoms). A series of Cox proportional hazard models were used to test the association between employment and mortality risk in the pooled sample and based on race, gender, education, and their intersections.

Results

Baseline employment in 1986 was associated with a lower risk of mortality over a 25-year period, net of covariates. In the pooled sample, baseline employment interacted with race (HR = .69, 95% CI = .49–.96), gender (HR = .73, 95% CI = .53–1.01), and education (HR = .64, 95% CI = .46–.88) on mortality, suggesting diminished protective effects for Blacks, women, and individuals with lower education, compared to Whites, men, and those with higher education. In stratified models, the association was significant for Whites (HR = .71, 95%CI = .59–.90), men (HR = .60, 95%CI = .43–.83), and individuals with high education (HR = .66, 95%CI = .50–.86) but not for Blacks (HR = .77, 95%CI = .56–1.01), women (HR = .88, 95%CI = .69–1.12), and those with low education (HR = .92, 95%CI = .67–1.26). The largest effects of employment on life expectancy were seen for highly educated men (HR = .50, 95%CI = .32–.78), White men (HR = .55, 95%CI = .38–.79), and highly educated Whites (HR = .63, 95%CI = .46–.84). The effects were non-significant for Black men (HR = 1.10, 95%CI = .68–1.78), Whites with low education (HR = 1.01, 95%CI = .67–1.51), and women with low education (HR = 1.06, 95%CI = .71–1.57).

Conclusion

In the USA, the health gain associated with employment is conditional on one’s race, gender, and education level, along with their intersections. Blacks, women, and individuals with lower education gain less from employment than do Whites, men, and highly educated people. More research is needed to understand how the intersections of race, gender, and education alter health gains associated with socioeconomic resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education, social status, and health. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2003.

Baker DP, Leon J, Smith Greenaway EG, Collins J, Movit M. The education effect on population health: a reassessment. Popul Dev Rev. 2011;37(2):307–32.

Morris JK, Cook DG, Shaper AG. Loss of employment and mortality. BMJ. 1994;308(6937):1135–9.

Eliason M. Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality following involuntary job loss: evidence from Swedish register data. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(1):35–46.

Noelke C, Beckfield J. Recessions, job loss, and mortality among older US adults. Am J Public Health. 2014 Nov;104(11):e126–34. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302210.

Brodish PH, Massing M, Tyroler HA. Income inequality and all-cause mortality in the 100 counties of North Carolina. South Med J. 2000;93(4):386–91.

Herd P, Goesling B, House JS. Socioeconomic position and health: the differential effects of education versus income on the onset versus progression of health problems. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(3):223–38.

Hummer RA, Lariscy JT. Educational attainment and adult mortality. International handbook of adult mortality. 241–261.

Masters RK, Hummer RA, Powers DA. Educational differences in US adult mortality a cohort perspective. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(4):548–72.

Brown DC, Hayward MD, Montez JK, Hummer RA, Chiu CT, Hidajat MM. The significance of education for mortality compression in the United States. Demography. 2012;49(3):819–40.

Dowd JB, Albright J, Raghunathan TE, Schoeni RF, Leclere F, Kaplan GA. Deeper and wider: income and mortality in the USA over three decades. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(1):183–8. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq189.

Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Do socioeconomic differences in mortality persist after retirement? 25 year follow up of civil servants from the first Whitehall study. BMJ. 1996;313:1170–80.

Broese van Groenou MI, Deeg DJ, Penninx BW. Income differentials in functional disability in old age: relative risks of onset, recovery, decline, attrition and mortality. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15(2):174–83.

Berkman CS, Gurland BJ. The relationship among income, other socioeconomic indicators, and functional level in older persons. J Aging Health. 1998;10(1):81–98.

Burgard SA, Elliott MR, Zivin K, House JS. Working conditions and depressive symptoms: a prospective study of US adults. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(9):1007–14. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182a299af.

Tapia Granados JA, House JS, Ionides EL, Burgard S, Schoeni RS. Individual joblessness, contextual unemployment, and mortality risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):280–7. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu128.

Roelfs DJ, Shor E, Davidson KW, Schwartz JE. Losing life and livelihood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):840–54. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.005.

Assari S. Combined racial and gender differences in the long-term predictive role of education on depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016.

Assari S, Lankarani MM. Race and urbanity alter the protective effect of education but not income on mortality. Front Public Health. 2016;4:100. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00100.

Assari S, Lankarani MM. Education and alcohol consumption among older Americans. Black-White Differences Front Public Health. 2016;4:67. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00067.

Garcy AM, Vågerö D. The length of unemployment predicts mortality, differently in men and women, and by cause of death: a six year mortality follow-up of the Swedish 1992–1996 recession. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):1911–20. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.034.

Mustard CA, Bielecky A, Etches J, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, Amick BC, et al. Mortality following unemployment in Canada, 1991–2001. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:441. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-441.

Farmer MM, Ferraro KF. Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):191–204.

Tsai SL, Lan CF, Lee CH, Huang N, Chou YJ. Involuntary unemployment and mortality in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103(12):900–7.

Gerdtham U, Johannesson M. Business cycles and mortality: results from Swedish microdata. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):205–18.

Novo M, Hammarstrom A, Janlert U. Do high levels of unemployment influence the health of those who are not unemployed? A gendered comparison of young men and women during boom and recession. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:293–303.

Martikainen PT, Maki N, Jantti M. The effects of unemployment on mortality following workplace downsizing and workplace closure: a register-based follow-up study of Finnish men and women during economic boom and recession. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):1070–5.

Mackenbach JP, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2468–81.

Martikainen P, Lahelma E, Ripatti S, Albanes D, Virtam J. Educational differences in lung cancer mortality in male smokers. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(2):264–7.

Steenland K, Henley J, Thun M. All-cause and cause-specific death rates by educational status for two million people in two American Cancer Society cohorts, 1959–1996. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(1):11–21.

Montez JK, Hayward MD, Brown DC, Hummer RA. Why is the educational gradient of mortality steeper for men? J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(5):625–34.

Zajacova A, Hummer RA. Gender differences in education effects on all-cause mortality for white and black adults in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):529–37.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16.

Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–8.

Ferri B, Connor D. Tools of exclusion: race, disability, and (re) segregated education. The Teachers College Record. 2005;107(3):453–74.

Roscigno VJ. Race and the reproduction of educational disadvantage. Social Forces. 1998;76(3):1033–61.

Gilman SE, Breslau J, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Subramanian SV, Zaslavsky AM. Education and race-ethnicity differences in the lifetime risk of alcohol dependence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(3):224–30.

Stoddard P, Adler NE. Education associations with smoking and leisure-time physical inactivity among Hispanic and Asian young adults. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(3):504–11.

Bound J, Freeman RB. What went wrong? The erosion of relative earnings and employment among young black men in the 1980s (No. w3778). National Bureau of Economic Research; 1991.

Annang L, Walsemann KM, Maitra D, Kerr JC. Does education matter? Examining racial differences in the association between education and STI diagnosis among black and white young adult females in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):110–21.

Chen E, Martin AD, Matthews KA. Understanding health disparities: the role of race and socioeconomic status in children’s health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):702–8.

House JS, Lepkowski JM, Kinney AM, Mero RP, Kessler RC, Regula Herzog A. The social stratification of aging and health. J Health Soc Behav. 1994;35(3):213–34.

House JS, Kessler RC, Herzog AR. Age, socioeconomic status, and health. Milbank Q. 1990;68(3):383–411.

Grossman M. Hanushek E, Welch F. Handbook of the economics of education. Vol. 1. Chapter 10. Education and Nonmarket Outcomes. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 577–633.

Brunello G, Fort M, Schneeweis N, Winter-Ebmer R. The causal effect of education on health: What is the role of health behaviors?. Health economics. 2015.

Liu SY, Chavan NR, Glymour MM. Type of high-school credentials and older age ADL and IADL limitations: is the GED credential equivalent to a diploma? Gerontologist. 2013;53(2):326–33.

Rosenbaum J. Degrees of health disparities: health status disparities between young adults with high school diplomas, sub-baccalaureate degrees, and baccalaureate degrees. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2012;12(2–3):156–68.

Zajacova A. Health in working-aged Americans: adults with high school equivalency diploma are similar to dropouts, not high school graduates. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):S284–90.

Liu SY, Buka SL, Linkletter CD, Kawachi I, Kubzansky L, Loucks EB. The association between blood pressure and years of schooling versus educational credentials: test of the sheepskin effect. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(2):128–38.

House JS, Kessler RC, Herzog AR. Age, socioeconomic status, and health. Milbank Q. 1990;68(3):383–411. doi:10.2307/3350111.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. doi:10.2307/2955359.

Lantz PM, House JS, Mero RP, Williams DR. Stress, life events, and socioeconomic disparities in health: results from the Americans’ Changing Lives Study. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(3):274–88. doi:10.1177/002214650504600305.

Gavin AR, Rue T, Takeuchi D. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between obesity and major depressive disorder: findings from the Comprehensive Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5):698–708.

Sherer M, Maddux JE, Mecadante B, Prentice-Dunn S, Jacobs B, Rogers RW. The self-efficacy scale: construction and validation. Psychol Rep. 1982;51:663–71. doi:10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663.

Harvey IS, Alexander K. Perceived social support and preventive health behavioral outcomes among older women. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2012;27(3):275–90. doi:10.1007/s10823-012-9172-3.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306.

Zhang W, O’Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JS, et al. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40793. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040793.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84.

Assari S, Lankarani MM, Burgard S. Black-white difference in long-term predictive power of self-rated health on all-cause mortality in United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(2):106–14. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.11.006.

Assari S, Burgard S, Zivin K. Long-term reciprocal associations between depressive symptoms and number of chronic medical conditions: longitudinal support for black-white health paradox. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(4):589–97. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0116-9.

Assari S, Moazen-Zadeh E, Lankarani MM, Micol-Foster V. Race, depressive symptoms, and all-cause mortality in the United States. Front Public Health. 2016;4:40. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00040.

Assari S, Lankarani MM. Depressive symptoms are associated with more hopelessness among white than black older adults. Front Public Health. 2016;4:82. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00082.

Assari S, Burgard S. Black-White differences in the effect of baseline depressive symptoms on deaths due to renal diseases: 25 year follow up of a nationally representative community sample. J Renal Inj Prev. 2015;4(4):127–34. doi:10.12861/jrip.2015.27.

Assari S. Hostility, anger, and cardiovascular mortality among Blacks and Whites. Research in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2016; doi:10.5812/cardiovascmed.34029.

Assari S. Race, sense of control over life, and short-term risk of mortality among older adults in the United States. Arch Med Sci. 2016; doi:10.5114/aoms.2016.59740.

Assari S, Lankarani MM. Chronic medical conditions and negative affect; racial variation in reciprocal associations. Fron Psychiatr. 2016; doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00140.

Assari S, Lankarani MM. Association between stressful life events and depression; intersection of race and gender. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(2):349–56. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0160-5.

Assari S, Sonnega A, Pepin R, Leggett A. Residual effects of restless sleep over depressive symptoms on chronic medical conditions: race by gender differences. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016; doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0202-z.

Assari S. Perceived neighborhood safety better predicts 25-year mortality risk among Whites than Blacks. J Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2016; doi:10.1007/s40615-016-0297-x.

Assari S. General self-efficacy and mortality in the USA; racial differences. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2016; doi:10.1007/s40615-016-0278-0.

Marks J, Bun LC, McHale SM. Family patterns of gender role attitudes. Sex Roles. 2009 Aug;61(3–4):221–34.

Oshio T, Inagaki S. The direct and indirect effects of initial job status on midlife psychological distress in Japan: evidence from a mediation analysis. Ind Health. 2015;53(4):311–21. doi:10.2486/indhealth.2014-0256.

Boardman JD, Fletcher JM. To cause or not to cause? That is the question, but identical twins might not have all of the answers. Soc Sci Med. 2015;127:198–200.

Reynolds JR, Ross CE. Social stratification and health: Education's benefit beyond economic status and social origins. Soc Probl. 1998;45(2):221–47.

Ross CE, Wu CL. The links between education and health. Am Sociol Rev. 1995:719–45.

Zajacova A, Everett BG. The nonequivalent health of high school equivalents. Soc Sci Q. 2014;95(1):221–38.

Link B, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(Extra Issue):80–94.

Darity WA Jr. Employment discrimination, segregation, and health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):226–31.

Amin V, Behrman JR, Spector TD. Does more schooling improve health outcomes and health related behaviors? Evidence from U.K. twins. Econ Educ Rev. 2013;1:35.

Paschall MJ, Bersamin M, Flewelling RL. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between college attendance and heavy alcohol use: a national study. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(2):266–74.

Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):269–78.

Mackenbach JP, Kulhánová I, Bopp M, Deboosere P, Eikemo TA, Hoffmann R, et al., EURO-GBD-SE Consortium. Variations in the relation between education and cause-specific mortality in 19 European populations: a test of the “fundamental causes” theory of social inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med. 2015;127:51–62.

Montez JK, Hummer RA, Hayward MD, Woo H, Rogers RG. Trends in the educational gradient of US adult mortality from 1986 through 2006 by race, gender, and age group. Res Aging. 2011;33(2):145–71.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):69–101.

Colen CG. Addressing racial disparities in health using life course perspectives. Du Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2011;8(01):79–94.

Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Seeman TE. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and health. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. 2004;310–352.

Everett BG, Rehkopf DH, Rogers RG. The nonlinear relationship between education and mortality: an examination of cohort, race/ethnic, and gender differences. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2013;32(6):893–917.

Masters RK. Uncrossing the US black-white mortality crossover: the role of cohort forces in life course mortality risk. Demography. 2012;49(3):773–96.

Phelan JC, Bruce G. Is race a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol. 2014;41.

Zarajova M. Why have educational disparities in mortality increased among white women in the United States? J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(2):165.

Read G, Gorman BK. Gender and health inequality. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:371–86.

Hayward MD, Hummer RA, Sasson I. Trends and group differences in the association between educational attainment and U.S. adult mortality: implications for understanding education's causal influence. Soc Sci Med. 2015;127:8–18.

Backlund E, Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ. A comparison of the relationships of education and income with mortality: the national longitudinal mortality study Soc. Sci Med. 1999;49(10):1373–84.

Everett BG, Rehkopf DH, Rogers RG. The nonlinear relationship between education and mortality: an examination of cohort, race/ethnic, and gender differences. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2013;32(6).

U.S. Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States. 128. Washington; 2009.

McCarrier KP, Zimmerman FJ, Ralston JD, Martin DP. Associations between minimum wage policy and access to health care: evidence from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1996–2007. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):359–67. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.108928.

McCarrier KP, Martin DP, Ralston JD, Zimmerman FJ. Associations between state minimum wage policy and health care access: a multi-level analysis of the 2004 behavioral risk factor survey. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2):729–48. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0284.

Acknowledgments

Shervin Assari is supported by the Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Research Fund and the Richard Tam Foundation at the University of Michigan Depression Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL) survey was funded by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, and National Institute on Aging (AG05561) and also Grant # AG018418 from the National Institute on Aging (DHHS/NIH). NIH is not responsible for the data collection or analyses represented in this article. The ACL study was conducted by the Institute of Social Research, University of Michigan.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocol.

Ethics

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Animal Studies

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Assari, S. Life Expectancy Gain Due to Employment Status Depends on Race, Gender, Education, and Their Intersections. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 375–386 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0381-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0381-x